Tasks of the Past, of the Present, and of the Future

In moments of feeling bogged down by various mess and miscellaneous tasks, I feel frustrated, and think about why it is that I “am so busy” – just what exactly am I doing, or what do I want to do? – and then I realise that the tasks can be categorised into tasks “of the past”, and tasks “of the future”. I’m sure there’s also some kind of task that is a task “of the present”.

Tasks of the Past

Reflections. Summarising. Tidying documents. Getting rid of stuff that is no longer needed.

These are the tasks that deal with “emotional baggage”, or “ego”, or “logical consistency”. By not doing them well and not doing them enough, the past feels like it’s weighing me down. I feel sluggish. Slow. Inefficient. Silly – why am I carrying all that stuff, and of what use is it all? – but indeed, much of it has much use; we just need to figure out which parts, and to distill it down.

Tasks of the Future

Studying. Exercising. Building new relationships. Maintaining (or growing) existing relationships. Working. Gathering resources. Building. Exploring. Doing repairs. Planning.

These are the tasks that grow our world: they make our world bigger; they help us to continue to exist. They are exciting; they give us energy. When we cannot do them, we become depressed: for we would no longer see our future.

Tasks of the Present

Well, the present is all there is, isn’t it? Haha, so, perhaps literally all tasks are “tasks of the present”, no? But there seem to be some tasks whose purpose relate more to the present than it does to the past or to the future: play, dance, meditation – although maybe these aren’t “tasks” as such.

Futures of the past

It’s a depressing thought, but it seems that as time goes on, as one ages, and as one’s future becomes smaller and smaller, and as one’s past becomes larger and larger – more and more of one’s tasks consist of Tasks of the Past than of Tasks of the Future. In the past, we had so many futures, that we couldn’t even comprehend the situation; in the present, sometimes it even feels like all that we will ever have has already been in the past.

Pasts in the present

“Life is Markov” – a toy statement that I used to play around with, back when they taught us about Markov chains (PDF): what might come next depends only on what exists in the present; what was in the past has already embedded itself into the fabric, into the details, and into the culture, mannerisms, memories, artifacts of the present. It seems encouraging to think of life as having the Markov property.

The past itself is of no use; in a sense, it doesn’t even exist. If we can only bring some of it into the present – some index, some snippet, some summary, some statistics, vibes, shadows, shapes, frustrations and excitements – then we should perhaps consider, which parts of the past do we actually want to embed into the present? (and those are the parts that would be carried forth into the future too.) Time that is borrowed from the future by ignoring the past, will inevitably have to be given back; but taking good care of the past is a way to invest in the future – “invest”, because the benefits are not immediate.

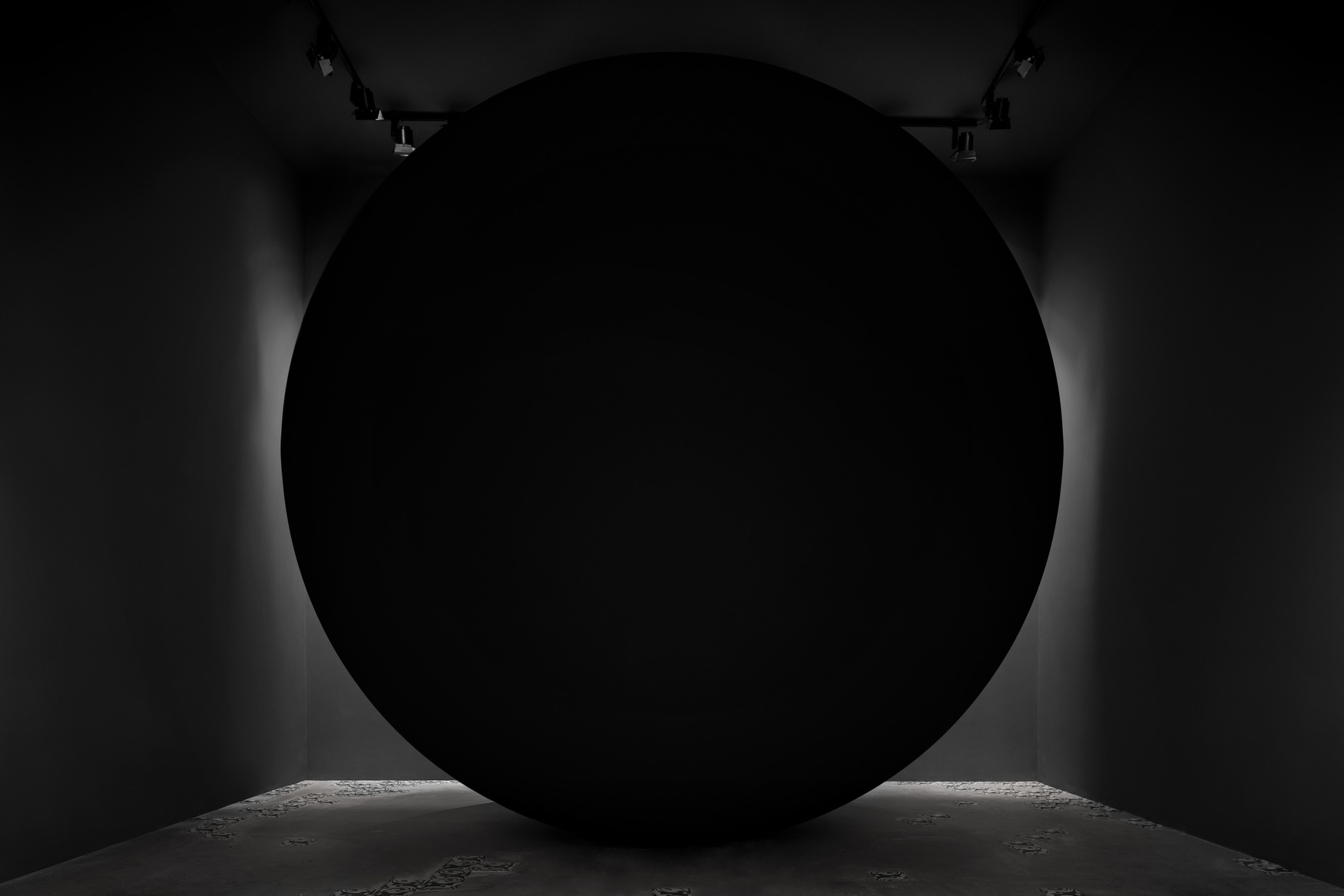

Monument for Lost Time

Monument for Lost Time (2019) is a piece of artwork by Palestinian-Danish artist Larissa Sansour. I didn’t know anything about this artist until I somewhat randomly ended up seeing the exhibition recently.

After first watching her film in the exhibition, In Vitro, in which something that looks like the Monument for Lost Time appeared on-screen, I was pretty shocked when I turned around a corner, and that the Monument physically appeared before my eyes. The low-frequency vibrations were harrowing. The large size of the thing was intimidating. I couldn’t see any texture on the surface of the Monument. I was a little bit shaken, staring into the abyss in front of my eyes.

I think being immersed in that room, in that exhibition, got me thinking about my own past and future: What can I remember, and what have I forgotten? What past do I still have with me, and what future might there still be?